In 2009, while Uber’s cofounders were gearing up to launch, a cadre of young Asian entrepreneurs-to-be entered the MBA program at Harvard Business School. Out of that group came two ride-sharing startups that would evolve quite differently than their American cousins. The company now called Grab was conceived by Malaysian students Anthony Tan and Hooi Ling Tan (no relation) as their entry in a business-plan contest. They didn’t win—but later, they wound up out-Ubering Uber in burgeoning cities across the 10-country ASEAN region in Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile, another classmate took a zigzag route to the top. Nadiem Makarim, working remotely with buddies back home in Indonesia, started Gojek as a side project while finishing his MBA. This ride-share app has branched into businesses from massage therapy to moviemaking. And just this week Gojek announced the largest business deal in Indonesia’s history, its merger with e-commerce giant Tokopedia. (Disclosure: Golden Gate Ventures is a small shareholder of Gojek via its acquisition of Ruma Mapan. We’ve also invested in Gojek’s spinout, GoPlay.)

Both Gojek and Grab are now venture-funded decacorns. Each is headed for a dual IPO on New York and Asian exchanges. And they’re racing to dominate much more than ride-hailing on Southeast Asians’ mobile phone screens. Grab and Gojek each offer what hasn’t yet been seen in the U.S. market: a superapp combo, featuring a payment app that’s a potential gateway to selling anything people may wish to buy.

Gojek’s Winding Road

Gojek began modestly in 2010. At first it was a “minimum viable product” venture—a local, low-tech operation led on a part-time basis by its faraway founder. The nascent company was just a phone-in/Twitter-in call center for booking rides with ojek (motorbike) drivers in Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta. That model didn’t promise high growth, but it gave the company valuable experience in working with drivers and customers.

As smartphone penetration grew, Gojek relaunched as a mobile app platform, aiming to expand. Founder Makarim was by then a full-time CEO but didn’t have much of a tech staff. So he contracted out the writing of the app to a development company, Ice House Indonesia. Despite this odd and somewhat dubious-looking tactic, Gojek was able to raise venture capital on the strength of its on-the-ground experience plus the size of the emerging Indonesian market. (It is the world’s fourth-largest country, with over 270 million people.)

And at this point Gojek defied the standard playbook for building an online platform company. The convention is to start with a focus on one type of product or service, then add others gradually. Amazon spent four years as an online bookstore before it segued into music and videos. Uber was five years old when it added Uber Eats. But Gojek, in a sense, had already done its single-focus homework. When relaunching as a mobile app, the company accelerated swiftly from minimum-viable-product mode to maximizing the variety of products. Ride-sharing was complemented with the delivery of prepared foods, groceries, and prescription meds. A key piece, the payment app, was added soon after, in April 2016. Drivers with cars and vans joined the motorbike brigade. Then came a blitz.

- GoPay, the payment app, has companion financial products such as insurance, investing, and more. The business group has been spun out semi-separately, similar to Alipay and Ant Financial from Alibaba. GoPay investors include payment giants Paypal, Facebook, and Google.

- In a striking move, Gojek branched into streaming entertainment. The GoPlay app streams Asian feature films and video episodes plus custom-made GoPlay Originals, named in a nod to Netflix Originals. These range from a Jakarta-themed remake of the U.S. teen series Gossip Girl to Filosofi Kopi (Philosophy of Coffee): The Series, spun off from a popular Indonesian movie.

- Gojek’s merger with Tokopedia will create a mega-company called GoTo. Interestingly, since Alibaba is an investor in Tokopedia while Tencent has a stake in Gojek, the new GoTo will have the dueling Chinese giants as co-backers on its journey to a public listing.

Previously, Gojek and Grab looked like prospective merger mates until those talks broke down. Soon to go public on its own, Grab is less diversified product-wise than Gojek but has a much larger ASEAN-wide presence, having used a different sort of approach to drive Uber from Southeast Asia.

Grab’s Winning Formula

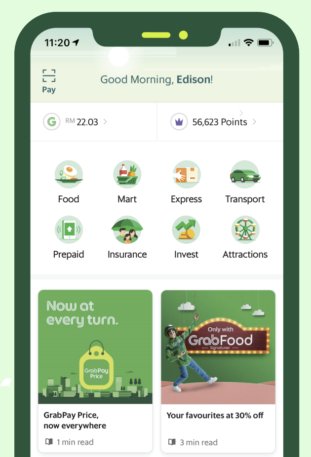

Whereas Gojek’s main advantage over Uber was its motorbike fleet—the nimble ojeks can weave through traffic jams and are cheap to hail—Grab prevailed with a strategy that combined rapid multinational growth with local sensitivity to each market. Grab used that combination to crack open one of the most valuable, yet nuanced and highly regulated areas in each country—payments and financial services. Not only is that product suite a nice potential revenue source—the payment app alone is super-valuable as an ever-flowing source of data on customers and their spending patterns. Mining the data can help target the marketing of any product or service imaginable.

In each new market, Grab presented itself as a partner to local taxi drivers and fleet owners rather than a foreign competitor, offering a platform that could help them find fares more efficiently. Grab catered to customers by accepting cash payments when Uber didn’t, and by emphasizing safety and reliability in cities where many people were once wary of even getting into a taxi. While Uber followed its U.S. payroll model of paying drivers biweekly, Grab realized many drivers in Asia required cash daily, even when customers paid by credit card. Grab first offered weekly payouts, then switched the drivers onto its GrabPay app, allowing them to be paid immediately after a ride.

Moreover, in each market Grab courted local investors and hired local tech and admin staff. This contrasted sharply with Uber’s reliance on American funding and imported American staffers. Local investors have been helpful to Grab in many ways, including securing hard-to-obtain ride-sharing and payment licenses. Local investors ensured that Grab prospered in the Philippines, while Gojek was denied a Philippines ride-sharing license a few years later in 2019. In Singapore, the government-linked fund Vertex provided Grab with significant early capital and access to the prosperous city-state’s market. Grab also relocated its HQ from Malaysia to Singapore, gaining a rich talent pool. And in many places, Grab sought investment from and sometimes hired members of wealthy conglomerate families. One example of a return perk: Through a relationship with owners of the luxury Shangri-La Hotel chain, Grab secured prime pickup lanes at the hotels.

Looking Ahead

Grab isn’t lacking big global backers either. Key investors include SoftBank and Uber itself, which swapped its ASEAN assets for shares of Grab when exiting the region. Once Grab and the Gojek-Tokopedia entity both get IPO cash, their rivalry will be something to watch. Perhaps most notably, the future of these two up-and-comers will serve as a test case for the future of the superapp business model.

Grab’s superapp cluster is leaner than Gojek’s but still potent, just by virtue of having the pivotal payment-and-finance core. But Gojek’s streaming entertainment could be a powerful trump card. What it buys is attention—engaging people to put your stuff on their screens to begin with, and keeping them engaged. And when the GoTo merger adds online shopping to the Gojek portfolio, that’ll create a force to be reckoned with.

With their superapp plays, both Grab and GoTo are aiming for territory far beyond Uber’s gambit of offering ride-sharing plus other forms of transport with a few burgeoning delivery services. This trajectory seems to make sense. Ride-sharing, wherever it’s been tried, seems best suited as a loss leader for building a user base to which to sell products. These two Asian giants have out-innovated their American counterparts by bundling services that drive financial performance higher, leaving traditional ride-sharing apps waiting at the taxi stand.

Vinnie Lauria is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur turned investor. He is a managing partner at Golden Gate Ventures, a Singapore-based VC fund.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.